Ganesh Chaturthi: From Tilak’s political strategy to Mumbai’s grand show

A sudden commotion on Mumbai streets announces 'his' arrival: a flatbed truck inching forward, carrying a garlanded, elephant-headed figure, staring serenely at the chaos around him. This is Ganesha, one of Hinduism’s most recognisable gods, celebrated less for cosmic power than for practicality, removing obstacles, blessing beginnings, presiding over exams and ventures alike. Ganeshotsav marks his annual descent to earth, a 10-day stay that ends with the spectacular Ganpati visarjan, when idols are immersed in the sea.

Once a private household ritual in 18th-century Pune, the festival grew into a public celebration under Maratha patronage, and later into a mass spectacle during India’s freedom struggle. Nowhere is this history more vividly on display than in Mumbai, where Ganeshotsav dominates the city’s imagination. Here, the god arrives not just in living rooms but in neighbourhood pavilions, in processions that paralyse traffic, and in idols so massive they seem engineered rather than sculpted.

Not just about religion but solidarity, nationalism

In the 18th century, Ganesh Chaturthi was not the roaring, drum-beating festival Mumbai knows today.

In Pune, it was an affair of clay and quiet. Families fashioned small idols by hand, placed them on wooden platforms in the courtyard, and offered flowers, oil lamps, and whispered prayers. The god, pot-bellied and elephant-headed, lived on the family altar, not the traffic island.

However, the shift began under the Peshwas, the Maratha rulers of the Deccan. As Ganesha was their chosen deity, they encouraged collective worship, bringing households together in shared rituals. What had once been a domestic devotion began to spill into neighbourhood courtyards. It wasn’t just about religion; it was about solidarity in an empire under constant threat. Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, doubled as a symbol of community strength.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak & Ganesh Chaturthi: What happened next

But the most radical turn came more than a century later.

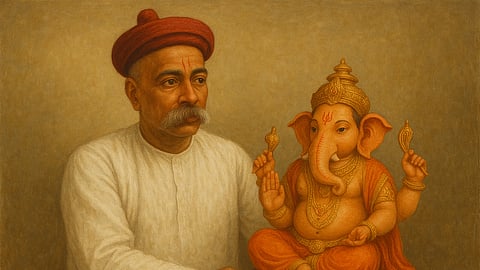

By the late 19th century, British colonial law had grown suspicious of Indians assembling in large numbers. Political meetings were curtailed; public speeches were heavily policed. Yet faith, unlike politics, was harder to ban. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a nationalist leader and founder-editor of the fiery Marathi newspaper Kesari, spotted the opportunity. In 1893, he called upon Pune’s citizens to celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi not within the four walls of their homes, but in public. And it worked!

Idols were installed in community spaces; bhajans and nukkad nataks were performed under open skies. Crowds gathered in the thousands, ostensibly to sing hymns to Ganesha. But as Tilak himself noted in his writings, the festival provided the best means of making the people familiar with the idea of nationality. In reality, speeches veered towards political unity, revolutionary ideas passed between neighbours, and slogans of self-rule were whispered in the same breath as prayers.

The colonial government could hardly shut down what looked like harmless piety. For the first time, a Hindu deity became a cover for insurgent thought. Faith was ritual, but it was also resistance!

Within a decade, Ganesh Chaturthi was being celebrated publicly across Maharashtra and parts of western India. From the Marathas’ courtyards to Tilak’s nationalist stages, the festival had reinvented itself as a collective ritual, equal parts devotion, theatre, and politics. What began as whispered prayers in Pune households had, by the turn of the century, become a roar in the streets!

From a quiet home festival to a sarvajanik utsav

Nevertheless, if Pune gave Ganesh Chaturthi its political teeth, Mumbai gave it its theatre. In Girgaon and Lalbaug, once the heart of 'Girangaon', with over 130 textile mills employing nearly 300,000 workers, the festival became the identity of the working-class. Mill labourers and fisherfolk pooled their modest savings to commission idols far too large for their one-room chawls. It wasn’t just devotion; it was a statement: we may be poor, but our god is grander than any landlord’s.

By the 1930s, community mandals had taken firm shape, raising funds door-to-door and staging processions that wound for miles through the city’s labyrinthine streets. The spectacle grew in tandem with the city itself. Mumbai’s newspapers from the 1940s describe processions that lasted all night, with brass bands and palkis carrying Ganesha idols through the mill districts.

Origins of Mumbai’s Lalbaugcha Raja

The best example of this transformation is Lalbaugcha Raja aka Navsacha Raja (meaning: a king who grants wishes), Mumbai’s most iconic idol. First installed in 1934 by fisherfolk and mill workers displaced from the Peru Chawl fish market, the idol was born out of a vow. The community had prayed that if they were given land to rebuild their market, they would honour Ganesha with a public installation. When the government allotted them a site within two years, they kept their promise. The idol was dressed as a fisherman and credited with “answering prayers”. Word spread.

Over decades, Lalbaugcha Raja grew into a phenomenon: queues lasting up to 24 hours, drawing industrial tycoons, film stars, and ordinary devotees alike. Whether or not the blessings come true, the sheer endurance of the wait has itself become a ritual.

More than a religious or cultural gathering

By the 1980s, Ganeshotsav in Mumbai was no longer just a religious or cultural gathering. It had become a stage for the city itself; its aspirations, its politics, its fractures. Political parties funded mandals, knowing that devotion translated into votes. Bollywood stars appeared at pandals for photo opportunities. Corporations began sponsoring the largest mandals, slapping their names on banners that hovered around awkwardly.

Mumbai's Ganesh Chaturthi: Arrival and departure, creation and immersion

For many Mumbaikars, Ganeshotsav is less about worship than participation. Millionaires from high-rises and daily wage workers from slums chant the same invocation: “Ganpati Bappa Morya”, as they wade into the water together after 10 days. The god, lowered into the Arabian Sea, disappears beneath waves already choked with a thousand other idols. The city watches its own handiwork dissolve.

There is an irony here, one that devotees embrace without complaint. You invite Ganesha in with a grand ceremony, feed him sweets, offer him songs, and then send him away. This cycle of arrival and departure, creation and immersion, is both ritual and philosophy: nothing we hold is permanent, not even a god made in our image. Yet its permanence lurks in memory.

To get all the latest content, download our mobile application. Available for both iOS & Android devices.